Whether or not you have been to the H. Cooper Black portion of the South Carolina state park system, or even if you are here, there are some things you may not know about it that you might find as interesting as I do. Also, you might have guessed wrong about a few things. I sure did!

My first visit here was this week, to assist Retriever News with its National Open Blog. My first misconception was thinking that the 2021 National Open would be somewhere around H. Cooper Black, not necessarily at the park, which is near the town of Cheraw, SC. I had booked an RV reservation here; so, I knew there would be campsites. To my surprise and delight, ALL ten series actually are at H. Cooper Black, as you may have figured out by now if you have been following the Blog. The 9th and 10th Series both will occur here tomorrow, as have the first eight.

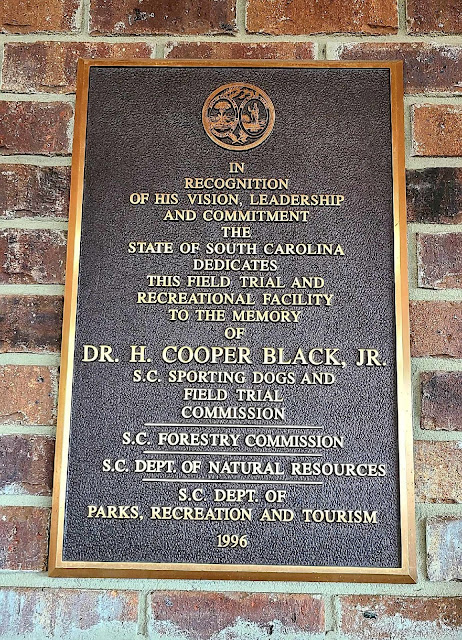

Officially, the full name of this area is H. Cooper Black Jr. Memorial Field Trial and Recreation Park. The park was created in 1996 in memory of Dr. H. Cooper Black, Jr, a member of the Sandlapper Field Trial Club and chairman of the South Carolina Sporting Dog Commission, who died in 1993. Had I known this long name that before my arrival, I clearly would have expected to find more than just a campground. The South Carolina Forestry Commission owns the property, which is leased by South Carolina Parks, Recreation and Tourism, Park Manager Eric Dusa has explained to me.

Four of the five dog training sites at this massive 7,000 acre property are being utilized for this National. The event sites known as Goose Pond, which is split into two training sites, and Mallard Pond are within close proximity to the campground. Palmetto Field is not, and the road to get there is not fun, unless you like a bumpy ride. I have no doubt that the dogs prefer very slow drivers to and from that venue. The fifth area, known as Wood Duck Pond, is not being utilized for this National.

The Park Service is attempting to add more training sites here, amounting to about 75 to 100 acres, by damming up a flowing creek. This first will require a ‘downstream site analysis,’ to make sure there are no adverse impacts. There is no charge because this is a state entity. Once created, these sites could be utilized for future Nationals.

The damming of creeks began, in earnest, in this area in the mid-1800s, mainly to create water for livestock. Eric has seen even older dams in the region. There even are some old water-fed grist mills still in service.

It may not be that obvious that the entire H Cooper Black Park is on sand; but, you can’t help but notice that all the main roads consist of it. I was very surprised to see so much sand this far from the Atlantic Ocean – 85 miles inland! Thirty miles to the west of the park is the “top of the Old Ocean Plain,” formed millions of years ago by ocean deposits. There is a major ‘soil morphological change’ from sand here to clay in the mountains, he adds. This property is a 240’ above sea level. Just thirty miles to the west, it is 660’ feet above sea level.

Perhaps even more astounding, in my opinion, is how deep the sand is on the grounds of this National. The sand extends 185 feet deep below us. There is no sand mining on the property; however, there are sand mines only about 25 miles away, mostly to the west.

If you ever tried to dig a hole in the sand at a beach, you know that sand, without water, will cave in on itself. So, you might wonder, how in the heck are the fabulous ponds here formed, and, just how do they stay put as ponds.

The sand here is ‘angular,’ says Eric. It is not ‘round,’ which will not pack, per se. The Eastern Coast has what is called ‘gumbo clay.’ It is very weathered, and like modeling clay. It clumps. What works here to keep the ponds in place is the vegetation that goes all the way to the edges of the ponds. “Vegetation is your best erosion control,” per Eric. There are no sandy beaches here. Despite the abundance of sand here, there are some clay pits. Sandy clay is used to build the dams and dikes.

Another clearly abundant natural feature of this property is its pine trees. The variety here is the Southern Long Needle Pine, which has the longest pine needles east of the Mississippi. This pine is native to the area; however, it was deforested in the 1930’s, then replanted in sections. If you look closely, you can see that they are planted in rows.

This property is in the northeastern corner of the Sandhill State Forest and is managed by the state parks system, which took over from the Forestry Service in 2007 and maintains thirteen square miles. The state Forestry Commission handles timber management, the roads, and the ‘pine straw.’ The pine needles are ‘gold’ that purposely are left on the ground in lieu of mulch. The grasslands are kept under control via controlled burns by the Park Service; whereas, the Forestry Commission does prescribed burns of the forest to help prevent forest fires. There are more than thirty miles of equestrian trails, and thirty-five miles of roads.

Dog training is allowed on the property; however, no live birds can be shot, except during official trials. Because the property is a bobwhite quail sanctuary, there is no bird hunting allowed here except for wild turkey. If that interests you, the season is only in April, annually.

The property hosts four field trials a year during which the entire property is rented. This includes the clubhouse and everyone involved is granted admission based on a flat fee per rental day. I found the ‘Admission Required’ signs a tad confounding. ‘Permission to Enter Required’ or something worded like that would be more understandable, I think. ‘Admission Required’ implies to me that a person must gain access. There are four types of ‘admissions:’ Daily, Yearly, which is via a ‘Park Passport,’ Day Leases, which really are half-days, from 6 am to Noon or from Noon to 6 pm for $35.50/each, and Exclusive Use.

Eric’s background seems ideally suited to his Park Manager position, which he has occupied since May 2018. He is one of the few people hired from the outside after the last Park Manager retired. For more than twenty years prior, he worked in Land Management, including management of a horse farm, which fits in well with the property’s horse activities. He had no prior experience in the canine world. “I didn’t know the first thing about dogs,” he admits; but, he said he quickly learned what he needed to know and is greatly interested in the dog activities here. Ironically, he holds a Bachelor of Science in Crop and Soil Science. The crop part is not particularly useful, as there is no farming in the area due to the ground consisting of sand rather than soil. And, well, there is no real soil.

H. Cooper Black is the only South Carolina state park available for retriever nationals and similar dog events. The current National is the fifth National Open to be held here. Previous years were 1997, 2001, 2005 and 2013. Per Eric’s recollection, there also have been two AKC Master Nationals, in 2015 and 2019, and the 2019 HRC Spring Grand. There also are regular Boykin Spaniel events and horse events. The Boykin Spaniel, btw, is the State Dog of South Carolina. I never in a million years would have guessed that!

Eric especially likes to have H. Cooper Black hosting Nationals because of the positive economic impact on the community. He adds that the South Carolina Park Service, which consists of 47 parks, is entirely ‘self-sufficient,’ meaning that it does not rely on tax dollars. He is pleased that people coming here from many other states precludes the need to tax the people of this state. Campground, property rental and retail sales comprise the bulk of the revenue. Regular admissions comprise only 3.% “This place has exploded in popularity since I’ve been here.”

“I want to thank the National Retriever Club and everyone who came out and supported us,” Eric notes. “We have a good symbiotic relationship.”

{This blog entry was submitted by Joule Charney.}